There are three variable that drive the financial return for Angel investors (and founders):

- Pre-Money Valuation.

- Subsequent Dilution.

- Exit Amount.

Instinctively founders seek as high a valuation as possible. It must be a ‘good thing’ to ‘give away’ as little equity as possible. Typically, founders will seek to find comparatives to justify their valuation proposals. If company X is worth $6m then we must be too. (Let’s put aside for the moment that the comparative being used is likely on a different continent, and probably has quite a different set of skills in its team, different experience in its founders, and different intellectual property).

And it seems many investors have been going along with this. Perhaps out of fear of losing out on ‘the best’ deals – though I have yet to meet anyone who can actually pick winners at the first round (or follow on actually) – if angels could do that then presumably the percentage of their portfolios that fail to return capital would be less than 70%.

A big part sems to be a failure to think strategically about a deal – looking not just at a first-round valuation, but at the total cash that business is going to need to get to an exit (and the resulting dilution on their ownership %), and the actual likely exit value achievable.

And this in turn is likely significantly due to the media fixation of Unicorns. Without appreciating that it’s the valuation of most unicorns that is a fantasy. Because so much talk is about $1bn companies that’s become the perceived normal – the bar against which all else is measured – and found wanting. But over the last 10 years just 1.7% of all UK high growth company exits have achieved a value of $1bn or more.

The unicorn culture has stopped people talking about, and admitting to, the reality – most exits are much, much smaller. And no, its not because we lack ambition in the UK – the exit values in the USA are largely at the same level. As with most commercial transactions the buyers have a price band they are comfortable paying. Trying to ‘scale’ past this comfort zone (which is a reflection of the acquirer’s commercial reality) is more likely to create a non-exitable company – and certainly massively dilute the early investors, and probably the founders as well – than crate added exit value.

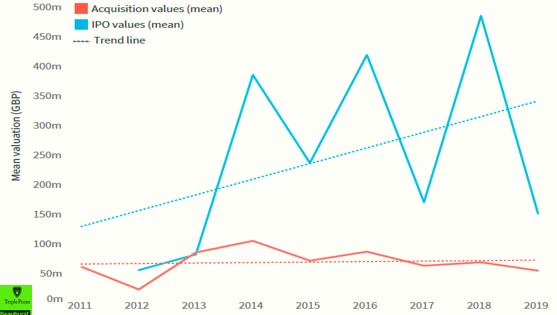

Triple Point and Beauhurst have produced a report looking at 2,724 exited UK companies between 2011 and 2019[1]. Of these they have exit value data on 604. It’s likely the bulk of the non-disclosed deal values will be at smaller values. Big deals are publicly announced (either publicly or in financial accounts). Small deal value announcements are likely inhibited by embarrassment under the prevailing unicorn culture.

The data shows that 87% of exit values are under £200m. But digging deeper, 51% are at £30m or less.

This is not a reflection of lack of ambition by UK founders – or a lack of UK scale up capital. The 2016 ‘Global Tech Exit Valuations’ report by CB Insights showed 54% of exits globally were at $50m or less (and they also pointed to the fact that the majority of smaller exit values are not made public, so that figure will likely be significantly overstated). Rob Witbank’s study presented to the American Angel Capital Association conference (ACA) suggested that 87% of US exit values were $50m or less (perhaps significantly impacted by the high level of ‘acquihire’ transactions, where a large tech company purchaser a small tech company just to get the technical team – the acquired company being quickly shut down. The technical skills of the team being seen as more valuable to the likes of Google than the product they were working on).

Exit value is critical in determining the financial return on all investments made into a company, including the very first. It’s hard to see how you can get the target 10x return from a deal (the generally agreed target needed to archive a 2 – 3x return at portfolio level given the very high, 70%, level of deals that will produce a negative return) if the first round valuation is north of £3 million, and the probable exit vale will be sub £50 million (even without considering any future funding dilution, or preferential returns introduced by subsequent funders).

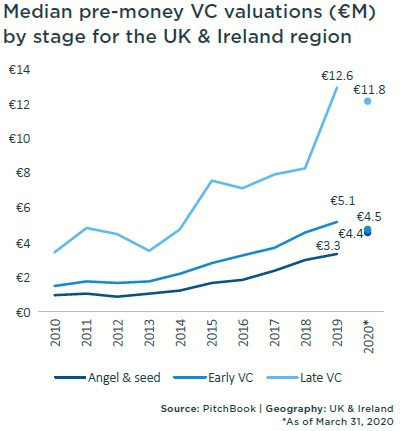

The report shows that 97% of exits have been via an acquisition (as opposed to an IPO), and the average acquisition exit value has remained unchanged over the past ten years. Yet data from Pitch Book shows entry valuations have been significantly increasing in the UK, with Angel and seed valuations rising from about £1 million in 2010 to £3 million in 2019.

Mean Acquisition Exit Values Flat over 10 years.

www.beauhurst.com/research/Exits-in-the-UK

There is no rational reason to accept an increase in entry valuations of 3x while exit values have remained flat. Perhaps it supply and demand – all that SEIS / EIS incentivised (dumb money) investment chasing quick deals to beat the tax deadlines. Perhaps it’s that before COVID chased them away Angel tourists thought it was cool to get into some ‘hot’ deals. Perhaps we investors have just not been looking for, and using, the realities of the data to negotiates sensible valuations, and been willing to walk away from the daft ones.

How do you calculate the ‘correct’ valuation? Comparatives have some merit, providing you are using a genuine comparative. Don’t go comparing your e commerce, shoe comparison site with a San Diego Biotech company. The Score Card method can help focus on the key issues to be used in due diligence, but if the management team is not excellent, you don’t compensate by lowering the valuation. You just don’t do the deal.

Truth is, startups have no value. How can they, if 70% end up failing to return capital (and obviously we don’t know which are in the 70%!). The 70% are probably worth less than zero at initial funding – because your going to lose money on them.

So how does valuation actually work? The early investors need to take 20-30% ownership to manage future dilution and have a decent ownership at exit, to derive that 10x potential return. This assumes a reasonable level of investment is going in, depending on location, say $100,000+. The valuation is derived based on that percentage, and the amount of funding the company needs to achieve credible, critical value add mile stones. If the company needs £500,000, and the investors take 25%, the post money valuation is £200,0000, and the pre £1,500.000. If the company needs £700,000, that valuation is £2.8m.

(The founders get the balance of ownership, less the 15% or so that is popped into the share option pool. Always get that set up at the time of your first investment – otherwise it will add further dilution when the next investor require it).

Is that £2 million valuation sensible? Depends on how much more cash needs to go in to get to exit, and the resulting dilution on the investors. That needs to be modelled on a future looking cap table, showing each expected future round, amount, valuation and dilution effect.

And then look to see what is the probability of achieving an exit big enough to get a 10x return. In simplistic terms, a £2 million entry with no further funding or dilution needs a £20 million exit. The data we have above suggest that 62% of exits are at values above £20m. Reasonable odds, as long as there is no more dilution. But it’s a rare company indeed that gets to exit, especially above £20 million, on a single round of funding.

This suggest that you would likely not want to be going above a £2 million valuation. And yet clearly the data indicates that investors regularly are. Perhaps all the higher valuations are for companies that are just that much more ‘special’.

Valuation is important, and does need to be considered in conjunction with future capital needs, dilution and the realities of exit value. Exit values of genuine comparatives, of similar companies in the same geography. And investing on the same terms. A valuation of £3 million is a very different value when the investor has a 3x preferential return built in.

[1] www.beauhurst.com/research/Exits-in-the-UK